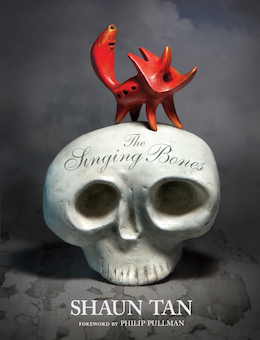

Shaun Tan, an artist whose oeuvre spans a variety of mediums but who primarily works in the fantastic genre, has just published a collection of photographs of sculptures based on the Grimm’s Fairytales. The handsome collection, small enough to carry and big enough to appreciate at length, is called The Singing Bones. Tan is not the first artist to tackle these stories, not by generations and continual fistfuls of illustration and reenactment, but sculpture isn’t the traditional medium.

With introductory material written by Neil Gaiman and Jack Zipes, the reader had a good sense of the project before delving into it. Gaiman addresses the emotional resonance of the pieces in his foreword—how it makes him want to put the stories in his mouth, like a child does. Zipes addresses the history—the Grimm brothers, their publications, and the traditional of illustration that made those publications as popular as they are today.

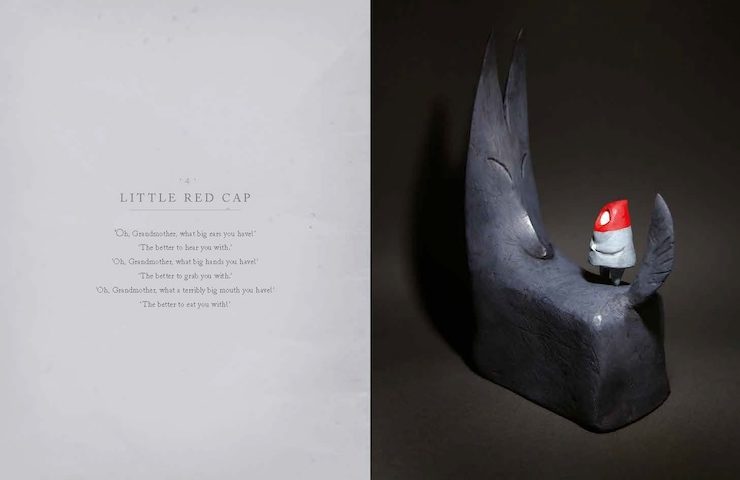

The choice of materials, as Tan described in his afterword, was also specific. Working in papier-mâché and air-drying clay on a small scale made him work primarily with his hands rather than separate tools. This gives the figures a distinctly human, almost “unpolished” appearance. He also uses coloration material like metal powders, shoe polish, and wax. Some pieces are luminous; others dark; others bright and daylit. The story drives the mood, and the mood echoes the story.

Having perused The Singing Bones at a leisurely pace, digesting chunks of it here and there, I suspect the best angle from which to consider it is as a companion: it is not a collection of illustrated fairytales, but a set of strange, almost primal figures paired alongside a fairytale. This structure relies on the audience to be familiar enough with the tale to place the concept from a brief paragraph, often no more than a handful of lines, and to appreciate the sculpture that goes with it.

There are summaries provided in the end, a sort of liner-notes section for the text, but those are an afterthought. However, for someone familiar with the Grimm’s Tales since childhood—for someone who knows them down to their own bones, even if not in perfect detail, perhaps moreso because of those nostalgic and possibly inaccurate recollections—this is a stellar artistic choice. It allows Tan’s sculptures to stand as separate works of art while simultaneously echoing the memories of the tales in a fashion that feels a bit more true to the oral tradition.

I’ve heard this story before, so I know it, but not quite like this.

It’s very much a book for coffee tables and for conversation, or a quiet evening flipping through the thick glossy pages to let each strange piece of art strike you one at a time. There’s something at once childlike and deeply skilled about the sculptures themselves: an intentional roughness but a clever and provocative set of staging choices around that roughness. The lack of specific detail, which the introductions point to, is designed to hook into those ur-tales in the readers’ mind rather than give them a specific figure to latch on to.

This doesn’t tell you how a princess looks; it shows you how it feels to think princess. Tan’s sculptures, then, are a sort of paraverbal or preverbal representation of the narrative. It’s eerie, to be honest, but eerie in a fashion that I certainly appreciated. The colors are vibrant at times, understated at others; the imagery of the sculptures varies from charming to discomfiting, handsome to a bit scary. The title of the collection—The Singing Bones—speaks to this strangeness: it’s getting down past the flesh to the skeleton of the story, the primal fears and wants and lessons of these oral-tradition pieces. Skeletons, though, are also symbols of mortality and fatalism.

For readers who aren’t familiar with the Grimm’s Fairytales collections, I would suggest perhaps a primer read first; while these are fascinating art pieces, the real work of this collection is in their reverberation across time and story. Without that second pole, there’s nothing for the knowledge to bounce back off of and illuminate dark thoughtful corners. It’s still gorgeous, but the work it’s doing needs that audience participation, as does much art.

Overall, it’s certainly a worthwhile purchase. It’s handsome, chilling, and thoroughly skilled. It’s also, as both introductions point out, one of a kind: Tan has decided not to illustrate the tales with specific figures but to present us the affect of the tales. And I’m very much down for that.

The Singing Bones is available now from Scholastic.

Lee Mandelo is a writer, critic, and editor whose primary fields of interest are speculative fiction and queer literature, especially when the two coincide. They have two books out, Beyond Binary: Genderqueer and Sexually Fluid Speculative Fiction and We Wuz Pushed: On Joanna Russ and Radical Truth-telling, and in the past have edited for publications like Strange Horizons Magazine. Other work has been featured in magazines such as Stone Telling, Clarkesworld, Apex, and Ideomancer.